Communication

Building from non-simultaneities: Mabubas Dam, Angola

Event: SAH Annual International Conference Albuquerque 2024

Authors: Ana Vaz Milheiro, Beatriz Serrazina

Date: 17 – 21 April 2024

Location: Albuquerque, United States

Summary

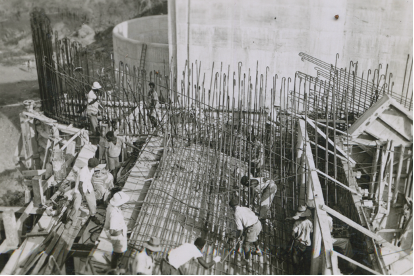

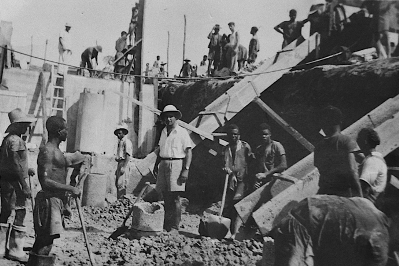

The Mabubas Dam, built in Angola between 1948 and 1954, was the first large infrastructural work promoted by the Portuguese state in Africa to sustain colonialism against the growing local and international scrutiny after World War II. Its 70-metre length, located in an isolated place near Luanda, resulted in an extensive and highly dynamic building site.

Acknowledging the political, social and technological circumstances in the Mabubas case, this presentation aimed to investigate the overlooked histories of colonial construction spaces to contribute to broader debates on building site conditions. As a fixed construction yard, later giving rise to a new settlement, the Mabubas Dam offers an intricate research ground, merging thousands of people, different tasks and labour hierarchies. Three significant relationships were explored: the intricacies between European and African workers, the tensions among African communities and the manifold interactions across the specialization strata, namely the hostilities towards workers from other colonial geographies, as the Cape Verdean labourers, considered more “civilized” and therefore more “skilled”.

Drawing from the thought-provoking “non-simultaneity” approach, by Heine and Rauhut, the presentation aimed to add new perspectives to the field from the peculiarities and complexities of colonial construction sites. While European building sites were based on familiar know-how systems and techniques, the construction spaces produced under colonialism arguably had a greater level of uncertainty, frequently exposed in reports. The colonial authorities did not control the traditional skills of the African communities nor the local materials, thus having to deal with unpredictable outcomes. Besides presenting a critical mapping of the colonial construction site, the presentation analysed its materialization in the archive. What information can be gathered in reports – from income to architectural design? What layers are absent (namely concerning women’s presence or building constraints)? How can these conditions contribute to more nuanced architectural histories?

Click here for more information.

Related Case Studies